The Hokkaran empire has conquered every land within their bold reach—but failed to notice a lurking darkness festering within the people. Now, their border walls begin to crumble, and villages fall to demons swarming out of the forests.

Away on the silver steppes, the remaining tribes of nomadic Qorin retreat and protect their own, having bartered a treaty with the empire, exchanging inheritance through the dynasties. It is up to two young warriors, raised together across borders since their prophesied birth, to save the world from the encroaching demons.

This is the story of an infamous Qorin warrior, Barsalayaa Shefali, a spoiled divine warrior empress, O Shizuka, and a power that can reach through time and space to save a land from a truly insidious evil.

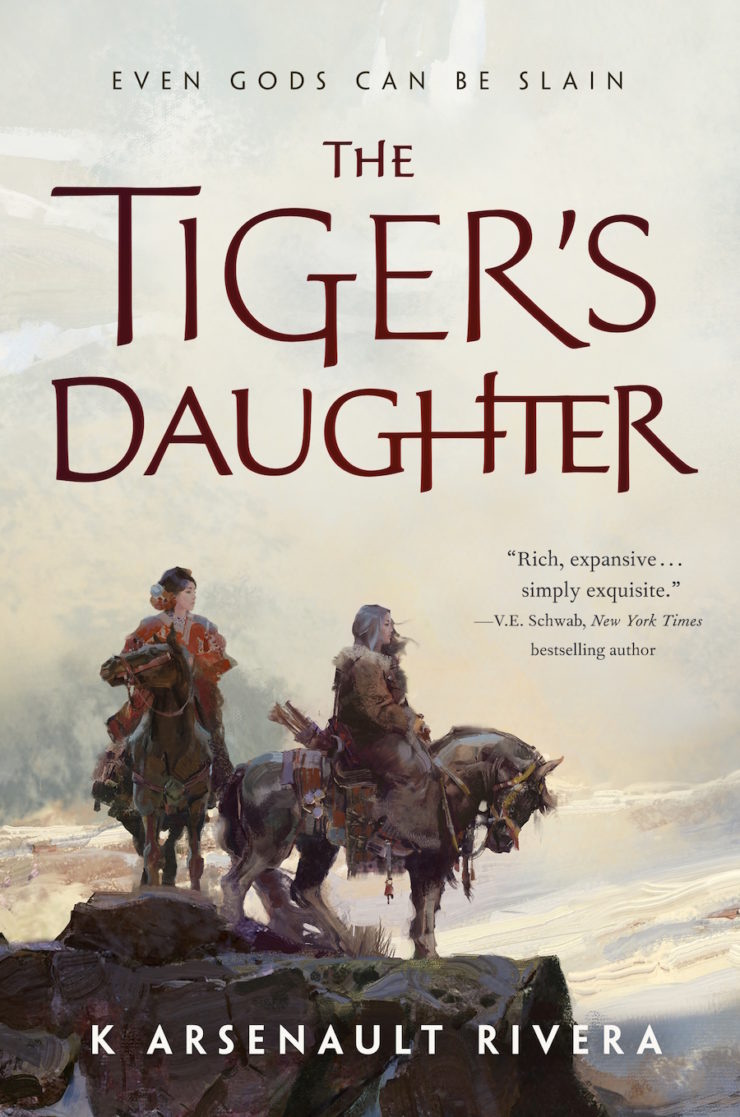

The start of a new fantasy series, K Arsenault Rivera’s The Tiger’s Daughter is an adventure for the ages—available October 3rd from Tor Books. Read chapter 3 below, and check out a full version of the illustration above from cover artist Jaime Jones. Come back all this week for additional excerpts—keep track of them here!

Three

On Our Mortal Lives

We stayed in that clearing that night. I urged you to let us ride back, or at least to ride toward somewhere a little better populated. But you insisted in your bullheaded way that we could stay wherever we pleased. After all, hadn’t you just told me that we were not normal?

I did not like that. It was the sort of thing said by a girl who has never had to keep watch for wolves in the dark of the night.

And so, as you crept into my tent to sleep, I set about bundling together our belongings and hanging them from a tree. Once this was done, I sat before the fire and resigned myself to a sleepless night.

It rained not long after you went to bed. My fire, reduced to smoldering cinders, did not give me much light. I slipped my arms inside my lined coat and huddled closer to the embers.

Yes, I remember the orange of the cinders, the low rumbles of the night creatures. I remember rain on leaves and their fresh green smell. I remember closing my eyes and listening to the hundred thousand sounds of life. I tilted my head back and let the rain fall into my mouth.

When it rained in the steppes, we’d put out every bowl we could to catch it. A hundred li away, my mother and cousins were running out into the darkness. They’d turn and dance and sing praises to the sky. In Xian-Lai—so far away, I could not imagine its distance— my father and brother slept in their warm beds. Kenshiro might be awake. Knowing him, he’d be sitting up in bed, looking out the window. In his hand I pictured a brush; on his mind, poetry. He kept writing to me of Lord Lai’s youngest daughter. Kenshiro said she was more beautiful than the wind through a silver horse’s mane, which might be the wrongest thing I’ve ever heard. How could he look on you and say such a thing about any other woman?

But love makes fools, as they say—and in my brother’s case, it drove him to write terrible courtship poetry.

Thick drops of rain fall like beats. One, two, three, four, five… And then there was you, asleep in my tent, not even a length away from me, yet given over to the world of dreams. I wondered what you dreamed of. I wondered if you were safe.

* * *

By the time dawn came upon me, my eyes were heavy with sand. I rose and moved toward the tent.

It was then that I saw the tiger.

You must understand I did not hear it, did not see it before this moment. A creature three, four times my size moved with the silence of death itself.

Your ancestor Minami Shiori hunted tigers for sport. Looking at the beast now, I did not know how she did it. Every sinew in its body, every muscle, tensed for attack. Great green eyes froze me in place. So astounded was I that I did not notice the beast was hurt.

Yes, yes, as it turned toward me, I saw dried blood on its paws like rust. On its side, a yawning mouth of a wound; on its side, claw marks. Red was its muzzle, red its teeth.

I did not know if tigers traveled in packs. I’d only heard of them in stories. There was only ever one tiger in the stories. Perhaps they were not like lone wolves, or lone Qorin.

But this one?

This one was. I knew that look in its eyes.

I licked my lips. The tiger crouched down. I’d seen cats do the same sort of thing, when they were about to pounce on mice.

I did what any Qorin would do: I mounted my horse and drew my bow, in a smooth ripple of movement. My palm still ached from the wound, but I did not have time to dwell on it.

“Shizuka!” I shouted. Hopefully, the sound of me raising my voice was enough to rouse you. If not, perhaps hooves pounding against the undergrowth would.

The tiger leaped forward, landing not far from me and my horse. In the moment before I kicked into a gallop, I found myself in awe. On the stepes we have only these animals: stoats, sheep, dogs, wolves, birds, and horses. For most of my life, I was surrounded by these creatures. I knew the best place to aim for when hunting a stoat. I knew how to skin a wolf. I could talk to horses, if I wanted.

But never in my life had I seen anything so graceful as that tiger. The Sun herself sang its praises, spinning gold from the orange of its fur, turning the black to brushstrokes. As it stalked us, I saw its thicmuscles sliding beneath its skin, like eels beneath a river.

We were wolves once, we Qorin—but there was nothing wolfish about that creature. When I looked into its great eyes, I did not see anything human. I didn’t see anything I recognized. How could something so large move with such fluidity? With those bright stripes, how could it hide in the forest? What did it eat?

It did not belong here, I decided. That was why it was so lean, that was why it was covered in battle wounds. Whoever the game master of this forest was had captured it and placed it here—but this was never its choice.

I frowned.

I knew, a bit, what it was like to be dropped into a forest you hate.

And so something about its terrible beauty was familiar to me, like a favorite song forgotten.

But it was trying to kill me. I could not admire it for long.

I loosed an arrow at it as my horse pulled ahead. With a satisfying thunk, the arrow pierced the beast’s pelt. A solid blow to its chest. A gout of blood watered the roots. The tiger roared, clawed at the ground.

And then it began running.

Riding through the forest is a difficult thing to do given the best conditions. Qorin horses are trained for speed and endurance, not sure-footedness. A good Hokkaran gelding would be ideal here. But I did not have a good Hokkaran gelding; I had a Qorin mare with a blackened steel coat and fire in her heart. As we barreled through the trees, I ducked low-hanging branches, whispered to her, told her we were going to make it out of this. I had to trust her. How else could I fire at the tiger? I could not guide us through the forest and aim. It was one or the other.

I thought of you scrambling awake in the tent. I thought of you watching the tiger follow me into the vast green growth.

Inside me was the thrumming power of a hundred horsemen; the light of a hundred dawns; the fire of a hundred clans meeting together. In the moment I realized this, a strange calm came over me. My horse could handle the woods, as long as I handled the tiger.

Another arrow, another, another. Each found its mark. First one of its paws, then its haunches, then its flank. Whatever agony the beast was in, it did not stop chasing me. My horse may be the fastest of the Burqila line, but it cannot outrun something that has lived and breathed this forest as I have lived and breathed sand and grass and snow.

The tiger jumped up onto a tree. I nocked an arrow.

Could I hit a target small as my palm while it was moving? Could I hit it while I was moving?

Could I hit it while seated? I loosed.

The arrow whistled through the air. There! It hit the tiger in the eye. The beast recoiled.

But it did not stop.

My heart hammered in my chest. It was going to jump. It was going to jump from the tree and it was going to land on my horse and me and there was nothing I could do to stop it.

I held her mane in my hand and flattened myself against her warm back. I took a deep breath and braced myself for what was coming. Would my mother be proud of me?

Wood creaking. The tiger, in the air. Claws tearing through my deel, tearing through my skin, baring my bone to the world. Red. Red. Red. Rank breath thick with the smell of corpses. Hot blood washing over my arm. A roar…

“Shefali!”

I forced my eyes open. You stood before us.

But how? Unless… Yes, this was the camp. My horse, wily as ever, had led us in a circle.

There you were with your blunted training sword, there you were standing tall and proud in the face of this horrible creature. I opened my mouth to shout at you, to tell you to run.

You charged ahead.

The beast, woozy from lack of blood, clawed at you. As fire crackling, you moved away.

I could not let you do this alone, no matter how much pain I was in. Drawing my bow was so agonizing, I thought I might pass out, but I could not allow myself to, not when you were in danger. My hands shook.

This would not hit. This was not going to hit. There was no way. I loosed.

Another arrow landed in the beast’s neck, near its shoulder.

You let out a roar to rival the tiger’s. Then you plunged your sword into its stomach.

I was dizzy, swaying, straining to open my eyes as my body fought to shut them. Coldness cut through me like winter’s harsh knife. Pain grabbed me by the shoulder and pulled, pulled, until my boot slid out of the stirrups and—

The last thing I saw before I fell off my horse: you under the morning sun, covered in the tiger’s blood, your dull blade alight with dawn’s fire.

When I awoke, you sat next to my bed. Worry lines dug their way onto your heart-shaped young face. Either your attendants had not seen you, or you did not let them touch you; the many knots and ornaments in your hair hung in disarray. Still you wore the red and gold dress.

“Shefali!” you said as you touched my shoulder. If I wore the ragged remnants of sleep, that touch and its resulting pain tore them off me. I screamed. You drew back and bit your lip. “I did not mean to hurt you,” you said. “It’s the tiger’s fault for wounding you there.”

I frowned.

You glanced away, hiding your hands within your wet sleeves. These were your rooms in Fujino. In each corner, a different treasure, given to you by a courtier to try to curry favor. A golden statue of the Mother. An intricate porcelain doll, dressed in identical clothing to yours. A calligraphy set. Fine parchments. Gold-

leaf ink. A bamboo screen, painted with O-Shizuru’s story.

“My mother will be here soon,” you said. “Be ready. She’s not pleased with either of us, though I imagine she will take it easier on you.”

I tilted my head, gestured around the room with my good hand. You understood me without my having to speak.

“After the incident,” you said, “I rode out to find the nearest guards. When I explained what happened, they followed me to camp. I carried you back and graciously allowed them to carry the tiger. My parents have no idea what to do with it. I have informed them that it is your decision to make, by any rules that matter.”

Your mother was not going to listen to that, and you knew it. But your father would. No doubt he found the whole situation poetic. A boon for us, then, if your father put ink to parchment in our behalf.

I pointed to my shoulder.

“Torn,” you said. “We brought in a healer. Not a very good one.” You shifted in your seat. Picked at your nails. At court, the latest fashion was to dust one’s fingertips in crushed gems mixed with oils and lotions. Between when I passed out and that moment,

you’d dipped yours in crushed garnets.

“She said that healing you was beyond her power,” you said. “It’s my opinion that if you call yourself a thing, and you cannot do that thing, then you are nothing at all. But that is my opinion. And as always, my parents do not want to listen to me. So the healer was compensated for her utter lack of work.”

With some effort—and some help from you—I sat up. Breath came in rattles.

When I was six, one of the Burqila clan riders came back from a hunt with his left arm in his right hand. His entire left arm. His left shoulder was a bloody stump; he and his horse were cloaked in rusty brown. Everyone ran to him. The women carried him off his horse and took him to the oracle’s tent. Two sheep were brought in, too, and I remember hearing the shrill cries they made. When my mother sent me to get the oracle’s blessings on her choice of camp a few days later, I saw the man. Sweat beaded on his brow like dew; fever painted his brown face red.

But his arm was attached again.

I reached for my own arm. It was still there. Why, then, was I beyond healing?

I thought of our promise again.

I grunted.

“I agree,” you said. “On the bright side, we do not have to attend court until you are healed.”

Small victories. Standing on my feet beneath a jade ceiling listening to Hokkarans prattle—was there any worse fate? At least they would not stare at me.

“Shizuka, you say that as if it’s a fitting reward for your foolish decisions.”

Ah. O-Shizuru opened the door. You sat a bit straighter, though I’m not certain you meant to.

“You will accompany me to court tomorrow. Your uncle has been asking about you, at any rate. Before the night is through, you shall write one of your father’s poems for him on fine white paper.”

You tugged at your sleeves rather than roll your eyes. If you rolled your eyes, you were lost.

Your mother was a force to be reckoned with when she was in the most pleasant of moods. Now worry and anger clouded her features. My mother may have conquered half of Hokkaro with nothing but horsemen and Dragon’s Fire, but bandits had whole rituals dedicated to keeping your mother at bay. Right then, I would’ve liked a ritual or two.

Your mother fixed me with a harsh, unyielding glare. Her brown eyes became slabs of earth, her mouth a canyon. “Shara,” said O-Shizuru, the only person who could call my mother that and live, “is never going to believe me.”

I drew back. The clouds broke; she cracked a smile.

“Two eight-year-olds attacked by a tiger, and neither of them dead,” she said. “If I told her that story, she’d give me a look, her look. And yet. Here we are.”

What was I to say to that? Not a word of it was wrong. Just— when she put it that way, we did sound foolish.

Your mother cleared her throat. “How is your shoulder?” I held up my hand and closed it tight into a fist.

She nodded. “Yes,” she said, “it’s going to hurt for some time. The healer couldn’t do much; the doctors say it’ll be at least a few months before you can shoot a bow with that arm again.”

Wrong. I’d be shooting a bow again within a few weeks at most. My young brain could not imagine a life where I went any longer than that without firing it.

“I’d ask you what happened,” said your mother, “but you’ve never been one for words. So I will tell you this.”

Now the solemnity crept back in; now her words were heavy as the first rain of the season.

“What you did was foolish. Beyond foolish. If a man strapped raw meat to his person and ran to the Emperor’s dogs—that would be less foolish. You are children; there are grown warriors who’d never dream of fighting a tiger. You lived this time. Next time, you will not. It is by the Mother’s intervention alone that you live.”

I wanted to say something. At the base of my throat, I felt it building. I wanted to tell her that, no, it was not the Mother’s grace, it was my own skill at riding, it was my horse, it was your blade striking the final blow. It was us.

But no, no, it was not the time.

So I sat. I sat and I listened as your mother outlined all the things we’d done wrong. As she told us again and again how foolish we’d been.

“There are bandits in those woods,” she said. “What would you have done if they came for you?”

“Shot them,” you said. However long she’d lectured you before I awoke, you could take no more. “She would’ve shot them, Mother. As she shot the tiger. Repeatedly.”

“Men are not tigers,” O-Shizuru snapped. “I’d rather fight a beast. At least they have dignity. Those men would’ve cut your horse’s legs out from—”

I yelped and drew the covers around my knees. My brown face went lighter, my mouth hung open, my breath left me in harsh gasps.

Your mother reached out a hand. No doubt it was meant to be reassuring, but the thought of my horse being hurt was still on my mind—the image of her crumpling as some godless bandit cut into her. Her cries of pain rang in my ears. I pressed my head against the pillows to drown it out.

You whispered something to your mother.

The Queen of Crows eyed me and sighed. “Shefali-lun,” she said, “no one is going to hurt your horse.”

I peeked out from my self-imposed exile and wrinkled my face. Your mother pinched the bridge of her nose. “Don’t give me that look,” she said. “You are on our lands. If anyone hurt your horse

while you were lying here, I would execute them myself.”

Slowly, slowly, I began to relax. But the look in her eyes still brooked no arguments.

“This changes nothing,” she said. “However incredible it is you slew the tiger, it was a foolish thing to do. You should’ve run, Shefali. You should’ve taken Shizuka up on your horse and the two of you should’ve gotten away, somewhere safe.”

I hung my head.

“People will tell you what you did was brave,” Shizuru said. “My husband among them. But you must remember how easily it could’ve gone wrong. This wound you bear will scar. When you feel stiff skin tugging in your shoulder—you will remember.”

And I drew the sheets closer to myself. I clutched them close. My throat tightened. So many things I wished to say. As she spoke, I watched you squirm in your seat. Each time you parted your lips, your eyes fell on my bandages, and you fell silent.

When your mother left, so did you. Urgent business, she said, that the both of you had to attend to. I watched you go. You looked back at me as you walked out of the room.

And then I sat up. I watched the moon rise. I thought of the tiger somewhere in the castle, rotting. What was I going to do with it? I’d never heard of anyone eating a tiger. An old Qorin poem came to mind. The Kharsa’s daughter has tiger-striped arms.… I could not remember the rest. I racked my brains for it, but I might’ve been milking a stallion for all the good it did me. Eventually my frustration surrendered to exhaustion. I fell asleep and dreamed of the steppes.

At least until you crept into bed next to me.

Still half asleep, I thought I must’ve dreamed you—your hair unbound, your skin flush with anger or embarrassment or…

“Shefali,” you said, lying next to me. How small you were for an eight-year-old, how tall I was. “I’m sorry.”

I must’ve been dreaming. “I should’ve moved faster.”

I must have been dreaming. Those words would never leave you in the waking world.

“I won’t let it happen again.” Sleep, then.

I went to court more than once. I did not like it. There, in the halls of jade, I was stared at by scholars and advisers and sycophants. “Ah, O-Shizuka-shon!” they might say, when they saw you. They’d bow so low that their beards swiped against the ground.

“The Tiger-Slayer! Heaven’s blood runs pure in you.”

“I did not kill the tiger,” you’d say. You said this each time we went to court, at least five times. “I struck the last blow, but I did not kill it.”

“Do not be so modest,” they might say. Or “Your humility is an inspiration.”

With a sharp gesture, you’d wave them away. Under your breath, you would mutter curses at them. A bit louder, you would apologize to me on their behalf.

But me?

“Oshiro-sun,” they might say, if they were being charitable. “Yun” was far more common from them than “sun,” as if I possessed the Traitor’s cunning simply for being born darker than they were. “Your father is a fine man, and your brother fares well.” But these courtiers never seemed to have any words for me. Nothing for Shefali. No praise. Did they know my name? Was I simply Oshiro to them? I must be. Not once during those summer months did I hear my personal name, save from your family. And that honorific—“sun.” I do not pretend to understand Hokkaran honorifics. Some things are beyond explanation. My people have twenty different words for the color brown, most of which relate to the color of a horse’s coat. Your people have eight sets of four honorifics, one for each god. Using the wrong one in the wrong context was as bad as spitting in the eye of a person’s mother right in front of them. To make matters worse, half of them sounded the same.

I knew only a few. “Sun” was the lowest form of the Grandmother’s honorific. Depending on the person speaking it, it might be affectionate. Most of the time, however, it indicated that the speaker thought themselves far above the subject.

The other ones I knew were “mor,” which was the highest for the Mother; “lor,” the second highest for the Sister and your father’s favorite; “tono,” used for the Emperor alone; and “shon.”

Shon was the Daughter’s highest. Who better to wear it than the girl born on the eighth day of the eighth month of the eighth year, at Last Bell?

You are doomed to be Shizuka-shon all your life, as I am destined to be Barsalai-sul for all of mine.

Honorifics were the least of our concerns, however. If we were annoyed by them, that meant we were at court, and if we were at court, there were other matters to distract us. Court itself, for instance. I had no clothes to wear. Your father was kind enough to buy me a new dress, for I was too tall to use any of yours. It was not so bad, for a Hokkaran dress—green, with painted horses along the sleeves and hem.

There was the matter of etiquette, of which I knew little. I solved that problem by letting you do all the talking, and bowing only when you glanced toward me expectantly.

And though it involved me little, there was also the matter of what people were saying.

* * *

As the space between a hammer and a pot, that was the court in those days. Emperor Yoshimoto could do little to stop the worries faced by his people.

“We will increase patrols along the Wall of Flowers,” he said.

Two weeks later, those patrols were found mangled and broken just outside the Wall.

“We will consult the oracles,” he said.

When the Hokkaran oracle was brought in to read the future in her vapors, she frothed at the mouth, screamed, and died on the gilded floor.

And then came Yoshimoto’s famous motto: “We will endure.”

It became something of a saying among the peasants.

A farmer struck his hoe against the ground—a new hoe he had made himself with fresh wood not a week ago. Sure enough, it would splinter. He’d pick up the metal end and heft it high overhead. After getting his wife’s attention, he would grin a sad, gaptoothed grin.

“We will endure,” he’d say.

A fisherman strikes out to sea. He takes with him a good net and a good rod. He sails far out and casts his net. Soon it is filled with pink salmon, flopping about, taking their last breaths. Just as he closes his eyes to thank the kami for his bounty, he smells something off. He opens his eyes.

The fish are rotten.

“We will endure” is his bitter laugh. Already the words began to haunt us.

* * *

Not long after I started healing, your mother left for another one of her missions. The magistrates out in Shiratori were having issues with a rebellion—they’d already caught the leader, but wanted your mother to make an example of him for the crowd. She did not look happy when she left—although your father managed to make her smile, whispering some secret promise in her ear.

Your father sat at the head of the dinner table and spoke blessings over our food. He teased you constantly. In his easy way, he would smile and call you the most read woman in Fujino.

“After all,” he said. “Your notices hang on every door. Your poetry is clear and simple, as refreshing as spring water—”

“Father,” you’d say, scrunching up your face as if you’d tasted something sour. “They are your brother’s words.”

For, yes, your uncle forced you to write all his notices. we will endure, eight hundred times each morning.

“Ah, yes,” Itsuki said. He held his teacup beneath his nose. Its sweet aromas filled his lungs and lent his smile a warmer air. “But your brushstrokes are the poetry.”

You palmed your face and I laughed. O-Itsuki watched you with a bemused look. This was how he always was: calm and relaxed, somehow above stress or worry. I cannot remember a wrinkle crossing his face, save for the lines winging his eyes when he laughed. And he laughed often. Whenever he and Shizuru attended court, he could not contain himself—always a twinkle in his eye, always some unheard joke rolling around his mind.

Many nights we passed like that, speaking with your father. The jokes were a welcome change from his brother’s proclamations. That was the year your uncle announced the eightfold path to plenty. All farmers had to bury specific stones attuned to their patron god in their fields—one every li, in each direction. For farms less than a li square, eight idols had to be buried, each oneeighth of the distance apart.

A superstitious gesture at best, meant to play on current fears. Your uncle claimed that it was Hokkaro’s lack of faith that prompted the Heavenly Family’s abandonment. Only proper veneration would bring them back. Anyone who failed to perform their pious duties would face Imperial justice.

Of course, burying things in a field like that, planting things the way he said to plant them, following all those rules…

I am no farmer, Shizuka. When I die and you leave me out for the vultures—that is the closest I shall come to farming, for flowers will grow where I last lay. But even I saw starving commoners curse your uncle.

Oh, when we were eight, it was not so bad. When we were eight, one could eke out a living, just barely.

But do you remember, Shizuka, when we traveled after—? I am getting ahead of myself. That part, too, will come.

I had my own set of rooms in Fujino, but that did not stop me from visiting yours. I slept in my own bed perhaps twice in the entire three seasons I was with you.

In the dark of night, when the moon was high, I worked on my project. I’d had the tiger’s pelt brought up to me. With my clumsy hands, I sewed and cut and sewed and cut. The end result was not going to be impressive—but it would be mine.

My mother arrived on the twenty-second of Tsu-Shao. With her came about a third of the Burqila clan, including two of my aunts. And Otgar, of course. I suspect she would’ve come even if she was in the sands at the time. I met them at the gates on my horse.

Otgar came riding up next to my mother. In the absence of my brother, she was a capable interpreter. All that time spent in our ger clued her in to my mother’s language of gestures.

“Needlenose!” she shouted in Qorin. “You live! I heard a tiger ate you!”

You blinked. You sat on your horse next to me. I do not think you’d seen other Qorin before, or at least not so many. Otgar’s loud, long greeting—several times longer in Qorin than it would’ve been in Hokkaran—might’ve startled you.

I waved at her as she pulled in. She clapped me hard on the shoulder and mussed my hair. A little over a year it’d been since I saw her, yet in that time she’d grown into her body far more than I had. Seeing her wide face, her red cheeks, her beautifully embroidered deel, made me feel more at home already. Then she took me close and pressed her nose against my cheeks.

She recoiled. “You smell like flowers!”

I laughed and pointed to you. You drew back.

“What is the matter?” you said. “Why was that girl smelling you?”

“To make sure she is the same Shefali,” Otgar said. Time lightened her Hokkaran accent; she almost sounded native. “Smell never changes, no matter how long she is with pale foreigners.”

Something changed in your posture. “You speak Hokkaran,” you said.

“I do!” she said. “I am Dorbentei Otgar Bayasaaq, and it is my honor to serve as Burqila’s interpreter.”

Next to us, our mothers exchanged their customary greetings. Despite the crowd, my mother embraced yours, held her tight, with her fingers in O-Shizuru’s hair.

But I was more concerned with what Otgar had said. “Dorbentei,” I repeated. “You are an adult?”

Otgar beamed from ear to notched ear, proudly displaying her missing tooth. “I am!” she said. “When I learned to speak Surian. No braids yet, but soon!”

“I am O-Shizuka,” you said, though no one had asked. “Daughter of O-Itsuki and O-Shizuru, Imperial Niece, Blood of Heaven—”

“Yes, yes,” said Otgar, waving you off. “You are Barsatoq. We know of you already, we have heard the stories.”

I tilted my head. Barsatoq. An adult name, like Dorbentei. But where Dorbentei meant “Possessing Three,” Barsatoq meant…

Well, it meant “Tiger Thief.”

I’m sorry you had to find out this way.

“So you’ve discussed me!” you said. Color filled your cheeks, and something of your old demeanor returned. “Yes, yes, I am Barsatoq Shizuka.”

I covered my mouth rather than laugh. Tiger Thief. My clan bestowed upon you the great honor of an adult name—something only a handful of foreigners received—and they named you Tiger Thief. You were so quick to embrace it! Someone must’ve told you what a mark of acceptance it is to be named by the Qorin.

And yet. Tiger Thief.

I was saved from hiding my amusement when my mother rode over. As animals sense storms, so I sensed her coming, and all the mirth fell from my face. My mother’s eyes were vipers, her quick gestures as fangs in my flesh. Otgar, too, lost her mirth.

“Shefali,” she said, “Burqila is displeased that you would act in such a foolhardy fashion.”

“She is your daughter, Alshara,” said O-Shizuru. “You are lucky she did not stuff the tiger with fireworks and set it soaring through the sky.”

Alshara shook her head. Another series of gestures, though less sharp.

“Burqila will host a banquet tonight, in her ger, to celebrate her daughter’s well-being,” Otgar said. “You are all welcome.”

Good lamb stew! A warm fire, with my clan sitting around it! My grandmother’s nagging; my aunts beating more felt into the ger; my uncles trying to convince them to do other things instead. The acrid smell of the fire pit, strips of meat hanging just above it to cure. Wind whistling outside, rattling the small red door. I’d get to see our hunting dogs again, too—how big were they now? The russet bitch must’ve had her pups.

And the kumaq. By Grandmother Sky, the kumaq!

I bounced in my saddle the whole way to camp, no matter how upset my mother was.

Home.

I was going home again.

Excerpted from The Tiger’s Daughter, copyright © 2017 by K Arsenault Rivera.